Code Reviews

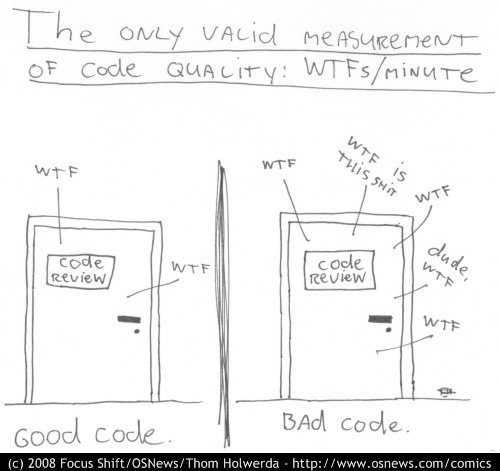

This comic always gives me a chuckle:

(Image by Thom Holwerda on OSNews)

Here we have two examples of code under a “closed door” code review. On the left is the “good code”, and on the right is the “bad code”. The main difference is that the “bad code” is getting significantly more reactions from the code reviewer. A huge stream of profanity can be heard from outside the door. The code reviewer doesn’t know what to make of what they are looking at. Anyone who has performed code reviews or read through any decent amount of code has had this experience.

But let me draw your attention to the other side, the “good code”. You’ll notice that the code reviewer has the same reaction, just less frequently. How can this be? This is the “good code”? Perhaps there is another reason why the code reviewer has a profanity-laced reaction to the code: a lack of understanding.

All developers assume that code they don’t understand is “bad code”. Show them a pattern they’re familiar with, written in a style that they like, and they’re happy. Show them something foreign and new, and they’re sad. “All of this needs to be rewritten.” “Throw it away!” If the developer spends more time with the code, suddenly there’s an a-ha moment. “Oh, I see; that’s why they did it that way. Makes sense.”

Case in point: early in my career, I was tasked with code reviewing a custom real-time interface system that had been written in VB6, which had encountered some issues. I was a full-stack web engineer and really had no basis for looking at this system. But, from management’s perspective, a developer is a developer, so I was the one reviewing. My feedback was scathing. Never had I seen such terrible code. Nothing made sense. It was obvious why we were having issues. My recommendation was to cast it aside and start over.

Years later, as I thought back on the code review and my feedback as I was exposed to more systems, I started to have a sinking feeling that just wouldn’t go away: I had been wrong. Yes, the system was written in VB6, which was considered old and outdated even at that time, but old technology doesn’t automatically make something bad. And yes, areas of the code were more difficult to read and understand what was happening, but perhaps that was due to my lack of experience at that time. After all, I had never written an enterprise system in VB6. I had never written a real-time interface in any language. I thought about how the system was divided into modules. How it used error code handling throughout. How much of the code had been carefully documented. This codebase had probably been a masterpiece of engineering. Yes, with a few bugs, but an excellent system all the same.

Code reviewers need to be skilled at reading code. They need to have familiarity with the patterns being used. They need to have a good understanding of the language and libraries. And it also helps a great deal if the code reviewer has experience in the domain of the system under review.

Another part of what makes code more difficult to read over time is that it has picked up a bunch of bug fixes. As Joel Spolsky writes in his post Things You Should Never Do, Part I:

Back to that two-page function. Yes, I know, it’s just a simple function to display a window, but it has grown little hairs and stuff on it, and nobody knows why. Well, I’ll tell you why: those are bug fixes.

Don’t just assume something is wrong. There may be a reason it is the way it is.

There is an interesting 11-post series of code reviews for the LMDB memory-mapped database library with back-and-forth between code reviewer Oren Eini (aka Ayende Rahien) and code author Howard Chu that illustrates some of these same points.