System Communication Patterns

There are three general styles of communication that can be used in systems: request/response, queuing, and eventing. Let’s explore these patterns.

Request/Response

Request/response is the general communication pattern (over) used in most systems. In a request/response style call, an operation is passed input parameters (the request), some processing happens, and output is returned (the result). Calling a method, calling an API, running a database query—these are all typical examples of request-response communications.

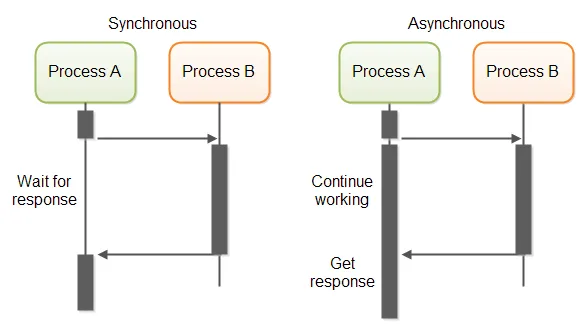

Request/response can take two forms: synchronous calls or asynchronous calls. With a synchronous call, the caller waits (or “blocks”) while the call is being processed. With an asynchronous call, the caller may continue to process locally while the call is being processed. The following diagram illustrates these two approaches:

(Image from here)

Keep in mind that an asynchronous call cannot just go on forever. Every hosting environment will set limits on how long a call can take, typically measured in seconds. A web service call will be timed out by the web server. A database query will be timed out by the database server. It is common for developers, when faced with operations that are timing out, to try and increase the timeout duration. This usually doesn’t work or introduces other issues. If it isn’t possible to increase duration, they may try to tune performance to make the operation run within the allocated timeout limit. But there is nothing to prevent the operation from running slowly and timing out in the future. Both of these approaches to addressing timeouts are likely incorrect and hint at the need to use a different communication pattern that can perform more reliably.

Queuing

Queuing is a fire-and-forget style of communication. A process issues a call (the message) to another process and then immediately resumes execution without waiting. This may sound similar to an asynchronous call; however, the queued call will never return a response. (Which also means no timeouts.) This works well when the caller doesn’t care about the outcome of the queued call. Messages flow through the queue in a first-in, first-out (FIFO) pattern. Each message is processed in sequence before moving on to the next message in the queue.

If a message is added to the queue that doesn’t match the expected format or has some type of error, it will be unable to be processed and will be marked as a poison message. By default on most platforms, poison messages will block further processing of the queue. Poison message handling should be setup to move the poison message to a separate poison message queue for further handling and allow the main queue to continue processing messages.

There are a few other important factors to consider. You need to ensure that a queue is not growing significantly faster than it can be processed. It’s also important to ensure that a queue does not exhaust available storage space. And there needs to be consideration given to what should happen to unprocessed messages in the event of a system or process restart.

In my experience, developers tend to be unfamiliar with queuing communication patterns. When faced with a fire-and-forget scenario, it’s not uncommon to see developers improvise a quasi-queue-like solution using a database table without realizing it. This wouldn’t be completely terrible if it weren’t for the fact that developers often feel the need to heavily normalize tables. The “queue” table ends up taking on too many jobs and becomes the only location in the database that holds the message data points. This prevents proper operation of the queuing pattern—messages should flow in and flow out of the queue. OLTP concerns should be addressed somewhere else. With this “queue” table approach, messages may flow in and never leave. All manner of flag columns are added to try and track what is going on with the database record. Synchronization issues arise on the flags. Reporting queries for other areas of the system are written off this same table. Table locking issues start to present themselves, which developers try to correct by introducing “nolock” directives. Poison message handling is nonexistent.

Eventing

When “something” happens in a system, this “something” (the event) can be communicated to interested parties (event listeners) throughout the system or even outside the system. This concept is known as eventing. Note that multiple event listeners can listen to and act upon a single event. Eventing can be implemented using a publish/subscribe pattern or with a technology such as web sockets. This communication pattern also works well for extending systems over time in ways that may not have been originally anticipated. New behaviors can be added to a system by adding a new component that listens for an event and performs a new action when the event is raised.

But what if an event is never raised? This could have two possible meanings: either the event hasn’t happened or something is broken. If a part of your system that is responsible for raising a certain event is not running, it will never raise an event. You need a mechanism in place to ensure that event-raising components are running and healthy in order to avoid this type of issue.

Developers also tend to be unfamiliar with event patterns and will resort to a polling approach, checking to see if something has happened. Polling isn’t terrible if it is done sparingly. But anyone with children knows the issues of polling. Polling too frequently or from too many sources can impact system performance. I’ve seen solutions that poll every couple seconds! Remember that “queue” table in the previous section? Imagine querying repeatedly to see if new records have appeared to be processed. Performance is terrible, and no one understands why. Checking for quasi-event-like records competes with trying to run reporting queries and general OLTP operations. The correct solution here is the same one you would use with your children on a long trip: “Stop asking if we’re there. Sit back. Relax. I’ll tell you when we’re there.” Invert the communication.

Simulating Long-Duration Asynchronous Calls

It can be useful to combine communication patterns together to overcome the disadvantages of one pattern with the advantages of another pattern. For example, instead of trying to run an asynchronous call for a very long duration by unsuccessfully increasing timeout durations, this same style of call can be simulated using a queued call to initiate the request and raising an event to provide the response at the end of processing. This type of approach has the advantage of a very long duration that will not timeout—instead of seconds, you could take minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, or even a year to respond if you need to.