Building Jarvis in C#, Part 4: The Push-to-Talk Button

Continuing the series on building Jarvis in C#, today we’ll be looking at a simple feature that we will build on further in a later post: the push-to-talk button. There are no speech-to-text capabilities yet, but rather just the button we will press to enable the speech-to-text feature once it exists. That’s right, this whole post is about one button.

Sometimes a language or a framework can be missing a feature that really leaves you scratching your head. The console in .NET has no concept of key-down or key-up events. So, when you want to build a feature that relies on performing an activity while a key is held down and then performing actions when the key is released, well, your work is cut out for you. Sure, you can detect key presses, but not the separate actions of down and up. .NET has this concept in other places, but not in a console app. (I suspect that they didn’t want to introduce an eventing model into the Console API for some reason. Although they did add a single event for ctrl-c/ctrl-break key combinations.) Yet another item that frustrates me with console app development. So, we’ll have to simulate key-down and key-up events with the tools at our disposal.

And I know what you’re saying. “Push-to-talk? Why not just use voice activation?” I don’t know about you, but I’m just not comfortable having a live mic constantly open in my house. I want to control when a mic is on and have awareness of what is being submitted to an external API.

Detecting Key Presses

So, with our mission identified, let’s take a look at the options provided by the .NET Console class for reading keyboard input:

- Read - Reads the next character from the standard input stream.

- ReadKey - Obtains the next character or function key pressed by the user. The pressed key is displayed in the console window.

- ReadKey(Boolean) - Obtains the next character or function key pressed by the user. The pressed key is optionally displayed in the console window.

- ReadLine - Reads the next line of characters from the standard input stream.

- KeyAvailable - Gets a value indicating whether a key press is available in the input stream.

- In.Peek() - Returns an integer representing the next character to be read, or -1 if there are no characters to be read.

And that’s it. Read, ReadKey, and ReadLine are all blocking calls. Program execution will wait until input is provided. In the case of Read and ReadLine, the enter key will need to be pressed. ReadKey will wait for any key to be pressed. KeyAvailable can detect whether or not a key has been pressed without blocking execution. Console.In.Peek() is strange. Reading through the documentation, you would think that peeking would work similarly to checking KeyAvailable, with the added advantage of knowing which key has been pressed. But Peek gives characters and not keys, with some keys not appearing in the character stream.

The only real option for detecting that a specific key has been pressed is to check KeyAvailable to determine if any key has been pressed, then use ReadKey to identify which key it was.

if (Console.KeyAvailable)

{

ConsoleKeyInfo key = Console.ReadKey(true);

//do something with key

}

Let’s see how we can use these limited options to produce key-down and key-up events.

The Push-to-Talk Finite-State Machine

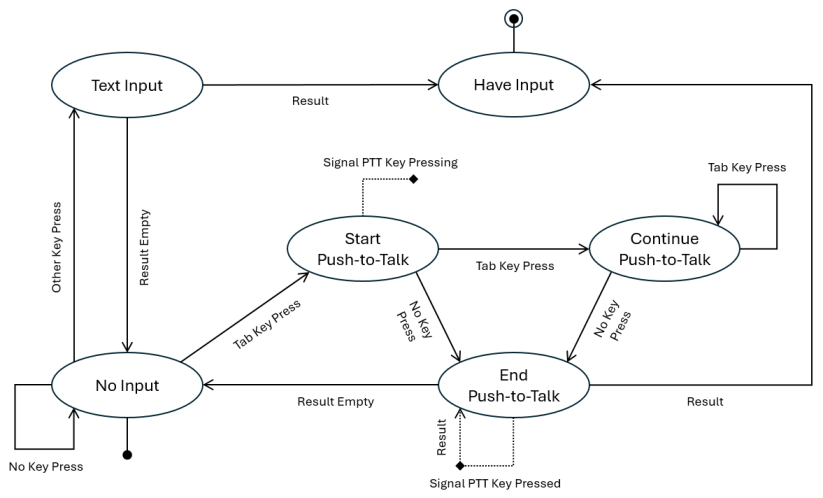

In order to simulate events for when the push-to-talk key is held down or released, we will combine the code for reading a key press from above with a finite-state machine.

(Push-to-Talk Finite-State Machine)

We start with no input. If a user presses the Tab key, we start pushing-to-talk. We signal to other parts of the program that the push-to-talk key is being held down using an event. As long as the Tab key is held down, a rapid series of Tab key presses will occur so that we can continue to be pushing-to-talk. Once the Tab key is released, all of the Tab key presses will get cleared away, leaving us with no key pressed. At this point, push-to-talk has ended. We signal to other parts of the program with an event that the push-to-talk key is no longer held down. We use a special event handler so that we can receive back a result with the user’s input. If the input is empty, we’re back at the no input state. But if the input is not empty, then we can move to the have input state and exit.

Now, what if the user pressed some other key at the beginning instead of the Tab key? Well, in that case, we are in the text input state. The user will type in the rest of their input. Once they hit the enter key, we check if the result is empty, in which case we are back at the no input state, or if the result is not empty, we move on to the have input state and exit.

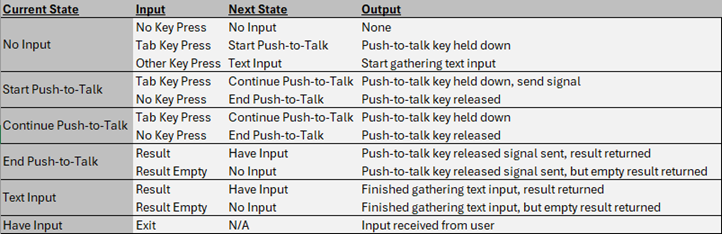

Here is a summary of these state transitions:

(Push-to-Talk State-Transition Table)

Now that we have a design for speaking input with a push-to-talk button and typing textual input using the keyboard, let’s build it!

The Input Loop

Before we look at the updated code, let’s review the original version from the first post in this series:

//Get user input

string? userInput = null;

while (userInput == null || userInput == string.Empty)

{

Console.Write(">> ");

userInput = Console.ReadLine();

}

Ah yes, it was a simpler time. We continually loop on inputs until we have some actual text from the user. In this case, we’re using the Console.ReadLine method. The user will enter a full line of text all at once and then press the enter key to continue. So, how might we adjust this structure to incorporate our state machine?

public string GetInput()

{

string? userInput = null;

Console.Write(">> ");

bool pushToTalk = false;

while (userInput == null || userInput == string.Empty)

{

//State: No Input

if (Console.KeyAvailable)

{

ConsoleKeyInfo firstKey = Console.ReadKey(true);

if(!pushToTalk)

{

if (firstKey.Key == ConsoleKey.Tab)

{

//State: Start Push-to-Talk

pushToTalk = true;

//Signal PTT Key Pressing

OnPushToTalkPressing(new EventArgs());

}

else

{

//State: Text Input

userInput = ReadLine(firstKey);

}

}

}

else if (pushToTalk)

{

//State: Continue Push-to-Talk

Thread.Sleep(1000);

if (!Console.KeyAvailable)

{

//State: End Push-to-Talk

pushToTalk = false;

//Signal PTT Key Pressed

string? text = OnPushToTalkPressed(new EventArgs());

Console.WriteLine(userInput);

}

}

}

//State: Have Input

return userInput;

}

Our finite-state machine in code. Bask in it.

I have stripped out some guarding logic here and there for edge cases and some on-screen indicators, which you can see in the full source code on GitHub, but this is the complete structure. Most of this is straight-forward based on my previous description, but I will comment further on the “Continue Push-to-Talk” implementation. The peeling off of repeated Tab key presses I mentioned in the above section is handled by the “ConsoleKeyInfo firstKey = Console.ReadKey(true);” line towards the top. And you’ll notice the “Thread.Sleep(1000);” line towards the bottom. I’m using this to jump the gap between the initial Tab key press and when the Tab key starts to auto-repeat. There is a little pause before the key starts repeating. If we were to immediately check for no key available, we’d erroneously determine that the user had let go of the Tab key when they were in fact still holding it down. I settled on 1000 milliseconds after some testing. I wanted to make sure I wasn’t cutting things short across different computers. It’s not perfect, and it does mean the key-up lags slightly after you actually release the key. But it feels okay. And I noticed a tendency during use to prematurely let go of the push-to-talk key while still talking, so the slight lag helps with this.

There are two events referenced in the above code:

public delegate string? ReturnStringEventHandler(object sender, EventArgs e);

public event EventHandler? PushToTalkPressing;

public event ReturnStringEventHandler? PushToTalkPressed;

protected virtual void OnPushToTalkPressing(EventArgs e)

{

PushToTalkPressing?.Invoke(this, e);

}

protected virtual string? OnPushToTalkPressed(EventArgs e)

{

string? result = null;

result = PushToTalkPressed?.Invoke(this, e);

return result;

}

Any parts of the system that want to be signaled when the Push-to-Talk button is being held down or when it is released can attach to the PushToTalkPressing and PushToTalkPressed events. You’ll notice that the PushToTalkPressed event makes use of a special delegate so that a string can be returned by the subscribing code. Since there will probably only be one event listener, I felt this was cleaner than having a mutable property embedded in the EventArgs or exposing a public property on the sender object that the consuming code would have to cast into.

Not everything is a happy story, though. With our approach to enabling key down and key up events, we inadvertently broke two things. Console.ReadLine() and the Backspace key. Let’s fix them.

Reinventing ReadLine

When we enter the Text Input state, the first letter of our input has already been read by the “ConsoleKeyInfo firstKey = Console.ReadKey(true);” line. If we use Console.ReadLine() at this point to get the rest of the text, we will be missing a character. That’s easy enough to fix. We can just include the extra key at the beginning of our return result. But this ReadKey method is also set to hide our first character when we press it. So, we’ll need to write the first key to the screen as well. Ok, no problem. Well, what if we decide to start using the Backspace key to remove our typing? All will be well until we get to this first character that we manually outputted to the screen. At this point, I decided that salvaging Console.ReadLine() wasn’t worth it. Let’s just rebuild it, and we can further expand this down the road with extra editing features like arrow keys, insert, and delete if we so choose as a side benefit.

So, we’ll be reading each key individually. Let’s take a look at that:

private string? ReadLine(ConsoleKeyInfo firstKey)

{

string? userInput = null;

List<char> inputBuffer = new();

if ((firstKey.KeyChar != 0) &&

(firstKey.Key != ConsoleKey.Tab) &&

(firstKey.Key != ConsoleKey.Backspace) &&

(firstKey.Key != ConsoleKey.Enter))

{

inputBuffer.Add(firstKey.KeyChar);

Console.Write(firstKey.KeyChar);

}

while(true)

{

var nextKey = Console.ReadKey(true);

if ((nextKey.Key == ConsoleKey.Backspace) && (inputBuffer.Count > 0))

{

//handle backspace

inputBuffer.RemoveAt(inputBuffer.Count - 1);

ConsoleBackspace();

if (inputBuffer.Count == 0)

break;

}

else if (nextKey.Key == ConsoleKey.Enter)

{

//finished entering message

userInput = new string(inputBuffer.ToArray());

Console.WriteLine();

break;

}

else

{

if ((nextKey.KeyChar != 0) && (nextKey.Key != ConsoleKey.Tab))

{

//add visible characters to buffer

inputBuffer.Add(nextKey.KeyChar);

Console.Write(nextKey.KeyChar);

}

}

}

return userInput;

}

We put the first key into the input buffer, skipping non-visible characters and special cases. Then we loop until the user presses enter. We add each visible key to the input buffer and write the key out to the screen. If the user presses Backspace, we remove the last key from the input buffer and then use the ConsoleBackspace method (which we will look at in the next section) to handle display concerns. If we delete all characters in the input buffer, we exit the method so that the user can do Push-to-Talk again if they so desire. If the user presses the enter key, then we are done entering text. We output the input buffer and exit the method. You may wonder why I am skipping the Tab key in several spots. If a tab is entered into the input buffer, it doesn’t play well with our ConsoleBackspace routine. So, I opted to skip it for now.

Speaking of the ConsoleBackspace method, let’s take a look at that now:

private void ConsoleBackspace()

{

var pos = Console.GetCursorPosition();

if ((pos.Left == 0) && (pos.Top == 0))

{

Console.Write(" ");

Console.SetCursorPosition(0, 0);

}

else if (pos.Left == 0)

{

Console.SetCursorPosition(Console.WindowWidth - 1, pos.Top - 1);

Console.Write(" ");

Console.SetCursorPosition(Console.WindowWidth - 1, pos.Top - 1);

}

else

{

Console.SetCursorPosition(pos.Left - 1, pos.Top);

Console.Write(" ");

Console.SetCursorPosition(pos.Left - 1, pos.Top);

}

}

There are three scenarios that have to be handled.

- The cursor is at the top left corner of the screen (this will probably never happen). Overwrite the character at that position with a space character, and then reset the cursor back to the top left.

- The cursor is all the way to the left of the screen. In this case, move the cursor one character away from the far right side of the screen and move up one row. Overwrite the character at that position with a space character and then move to the left one character

- And finally, the cursor is somewhere in the middle of the screen. Move the cursor to the left one character, overwrite the character with a space character, then move back to the left one character again.

And presto, we have a Backspace key again.

Conclusion

Well, we’ve done it. We’ve successfully added a push-to-talk key. It doesn’t do much yet, but we have it. In a future post, we’ll be able to wire up speech-to-text capabilities for these new events. In addition to the changes discussed in this post, I’ve also taken the opportunity to start refactoring the code into separate classes.

For Jarvis’s full source code, feel free to check out my GitHub repository here. All code was written in C# 10 on .NET 6 using Visual Studio Code and the C# Dev Kit extension on Linux, also tested in Visual Studio 2022 on Windows.